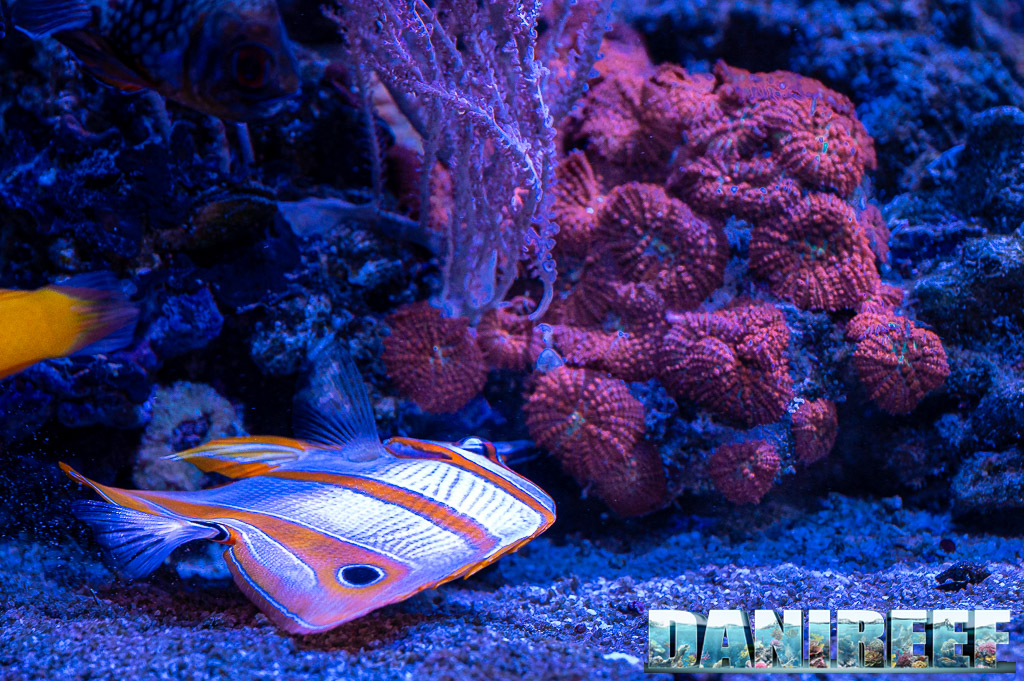

The Chelmon rostratus enchants with its golden stripes, yet it remains a delicate and demanding marine fish to keep… could it really be the solution against Aiptasia? Let’s find out if its reputation is deserved.

The Chelmon rostratus is one of the most fascinating butterflyfish an aquarist could wish for. However, behind its beauty lies great fragility: it is a delicate animal, often difficult to acclimate and maintain. At the same time, it has the — partly deserved — reputation of being a relentless Aiptasia eater. Let’s see if that is really the case.

Chelmon rostratus

The Chelmon rostratus, as we mentioned, belongs to the butterflyfish family (Chaetodontidae). It is also known by the common name Copperband butterflyfish thanks to its characteristic elongated snout. It is closely related to other butterflyfish: the family currently includes 128 species divided into 12 genera. Most of them share the same irresistible appetite for Aiptasia, though they also show interest in Tridacna clams and, in some cases, various corals. There are, however, some important exceptions we will discuss further.

The Chelmon is an incredibly beautiful fish. Just looking at it makes you fall in love. Watching it swim with its distinctive sinuous movement makes you want one in your tank. And if we add the fact that it is a tireless predator of Aiptasia and majano anemones, we get the portrait of the perfect fish. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to acclimate and feed. Moreover, it is often hard to find in good health, as it is one of the species most frequently collected using the destructive technique of cyanide fishing. If you want to learn more about this, we wrote an in-depth article: Cyanide fishing could be avoided: here are the latest research updates.

As if that were not enough, like its relatives, it is dangerously attracted to Tridacna clams and coral polyps, often targeting soft corals and LPS, and occasionally SPS. This makes it a gamble in the aquarium. Many Chelmon arrive unhealthy, often dying within ten days of introduction due to liver damage — not the aquarist’s fault. Those that do survive, after clearing Aiptasia and majano anemones, often begin to nip at corals too.

What are the chances that Chelmon rostratus will eat Aiptasia?

The Chelmon rostratus in the great majority of cases feeds on Aiptasia and also on the equally invasive majano anemones. Not every individual shows the same appetite, but it is rare to find one completely uninterested. From this point of view, if you are looking for a fish to take care of these pests, you may have found the right one.

What are the chances that Chelmon rostratus will eat corals?

This question also has a fairly obvious answer. It will. Although it depends a lot not only on the individual fish but also on the type of coral. If you notice your corals’ polyps remaining retracted even when they shouldn’t, then you know where to look. That’s a clear sign that someone is bothering them. From this point of view, the issue with SPS corals such as Acropora, Montipora, Stylophora, Pocillopora is far less severe, as they have small polyps that are less attractive to it.

However, it should be noted that in a large aquarium heavily populated with corals, the damage it may cause to SPS is usually limited. Since it prefers other prey, corals often have time to regrow.

Tridacna clams, on the other hand, should definitely not be kept with Chelmon rostratus. They can quickly lead them to death by pecking and disturbing them, even damaging the byssus in the worst cases. The same applies to soft corals, zoanthids, and LPS corals. They can be heavily damaged, especially if the Chelmon keeps focusing on the same colony without giving it time to recover.

The Chelmon rostratus is not a large fish, but in nature it can grow up to 20 cm (Scott W. Michael and Fishbase). It therefore requires space, hiding spots, and plenty of benthic fauna to forage all day. It is not an aggressive species and usually lives peacefully with others. However, it does not like being housed with fish of similar coloration; even the Zebrasoma flavescens may become a problem. A larger tank always helps. Keep in mind, though, that the Chelmon rostratus has no real means of defense when encountering surgeonfish.

Distribution

The Chelmon inhabits the western Indo-Pacific Ocean: from the Andaman Islands to the Ryukyu Islands in Japan, and of course throughout the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. It is usually found between 1 and 25 meters deep near reefs.

Behavior and recommended tank size

The Chelmon rostratus is not a large fish, but in nature it can reach up to 20 cm (Scott W. Michael and Fishbase). It therefore needs space, hiding places, and lots of benthic fauna to forage throughout the day. I recommend a marine aquarium of at least 300 liters, but if the tank is heavily stocked with corals, 500 liters or more is preferable to reduce the likelihood of damage. It is not aggressive and generally coexists peacefully. However, it can become aggressive toward conspecifics. It is possible to keep a male-female pair or even a large group in huge aquariums, where dominance is established by size, but in home aquariums this is strongly discouraged.

How to maximize chances of success

As mentioned, the Chelmon rostratus is a very delicate fish. But there are some tricks to keeping it successfully. First of all, to avoid issues from cyanide fishing and to promote responsible aquarism, you should look for a captive-bred specimen. Honestly, I don’t know if they are available in the trade yet, but they were successfully bred in 2021 by Rising Tide after four years of effort. You can read the full story here: Chelmon rostratus successfully bred in captivity.

Otherwise, always aim for a specimen that has been quarantined in the store. This is the only way to avoid bringing home a fish collected with cyanide or already severely weakened.

Even then, keeping the Chelmon rostratus in captivity is notoriously complex, and the resilience of individual specimens varies greatly. Some adapt quickly and begin eating fresh or frozen food within days, while others refuse to feed and eventually starve. In such cases, it may be necessary to resort to live food, such as small clams or mussels opened, or live mysis and brine shrimp to stimulate their appetite.

An interesting aspect is the origin: specimens collected in Australia seem to adapt better to captivity than those exported from the Philippines, likely due to different collection and shipping methods. Some aquarists have reported that particularly colorful individuals from Asia may have been caught with cyanide, which compromises long-term survival, although this hypothesis has not been scientifically confirmed.

It is also essential to avoid purchasing specimens that are malnourished or emaciated, as they rarely recover. It also seems that smaller individuals (around 7.5 cm long) adapt better than larger ones. In optimal conditions, the record for this species in captivity is about 10 years.

Did you know?

The Chelmon rostratus is one of the few marine fish that in the wild are often observed in stable pairs. These are not just temporary groupings but true pair bonds that can last a lifetime — a rare behavior among butterflyfish. In aquariums, however, housing two usually leads to aggression until one perishes, while in the wild they form inseparable couples that patrol the reef together in search of small invertebrates.

DaniReef’s advice: HIGHLY RECOMMENDED only for aquarists who know exactly what they are doing. Special feature: stunning beauty!

Have you ever kept a Chelmon rostratus? Share your experience in the comments below and on our social channels! Follow us on Telegram, Instagram, Facebook, X/Twitter and YouTube to never miss other articles and video reports from the marine aquarium world. And if you need help with the Chelmon or any other aspect of reefkeeping, join us on our forum.

Scopri di più da DaniReef - Portale dedicato a Acquario Marino e Dolce

Abbonati per ricevere gli ultimi articoli inviati alla tua e-mail.